My ancestors in the Imperial Valley achieved hard-fought victories that will be celebrated years to come, but they came at a cost. It was a painful history that must never be forgotten. I, along with many others, inherited that pain, but we also carry the responsibility to learn from it, to let it inspire us, and to create a better future for the next generation.

I grew up in this valley, born in Brawley, during a time in history that I, and many others, didn’t fully comprehend. My grandmother, Mary Garcia, never sat me down to share stories about working the fields. At school, my classmates and I once watched a long, boring César Chávez documentary. I nodded, shrugged, and moved on. That kind of detachment stuck with me until I was an adult.

Some people leave Imperial county, while others stay, both with the same sense of not caring. In conversations, I used to nod along about this place not being all that. And sure, nothing is perfect, but something changed this year. Now, I care about this place more than ever before, about all the untold stories, the people I haven’t met yet, and the history that raised me when I didn’t even realize it.

Source: Library of Congress

I knew I was born into a Filipino family from Niland, but I never really cared enough to ask more questions about it. I guess you could say I never fully identified as Filipino, and it was only recently that I started piecing everything together. This year, I learned about how important my family’s story is to the history of this valley, and also to my own.

So back to my grandma, Mary. She never wanted to share her field working stories because…

Grandma Mary didn’t want to burden me or my siblings with sad stories. That wasn’t her style. But this time, when I asked about her past, she was more willing to open up. She told me she started working in the fields near Niland at age 14, picking squash, handing off watermelons, and planting various crops whenever there were school breaks. In the early 1970s, she worked in the fields at Mecca, picking grapes alongside other Filipino laborers. Protesters would call her a “Filipino lover” to try to recruit her. But when it came to the César Chávez demonstrations, her boss saw them as a threat and warned workers not to join. She once saw someone fire a gun into the air, which scared her and made her decide to stay away from those protests.

This is how Mary got to work: she’d wake up at 4 a.m. and drive her red 1975 Camaro to the fields, arriving by 5 or 6 in the morning. She worked all day until sunset. To give it some more perspective, in the 1960s and ’70s, wages were as low as 80 to 90 cents an hour. Even while pregnant with my mom, she kept working in the fields, sorting squash alongside her husband at the time, my grandfather Freddy Orsino.

Mecca was where the protests took place, where she remembered harshly being told to leave the fields by the protesters. But with four kids to feed, she couldn’t afford to stop working. She wasn’t eligible for welfare and was even accused of hiding her husband’s benefits. It got to a point where she was told to divorce him to qualify for assistance. Eventually, she met the grandfather I grew up with, Ruben Garcia. He supported her and her four kids without relying on aid. Looking back, she wonders if she should have joined the protests, given the rights and benefits farmworkers have now, but at the time…

This year, I attended a meeting for the César Chávez march. That’s where I met Max Reyes, the leader of the César Chávez March Committee, and reconnected with Cecilia Gastelo, a local volunteer who is just as passionate about the Imperial Valley as Sarina and I. One by one, more people arrived: my former art teacher Caitlyn Chávez, her husband Miguel Chávez, the Chicano Studies professor at Imperial Valley College, and many others. Women who had once served food to César Chávez and farmworkers were also present. One family member, Dianna R. Morales, shared her story with me, one I’ll discuss later in this story.

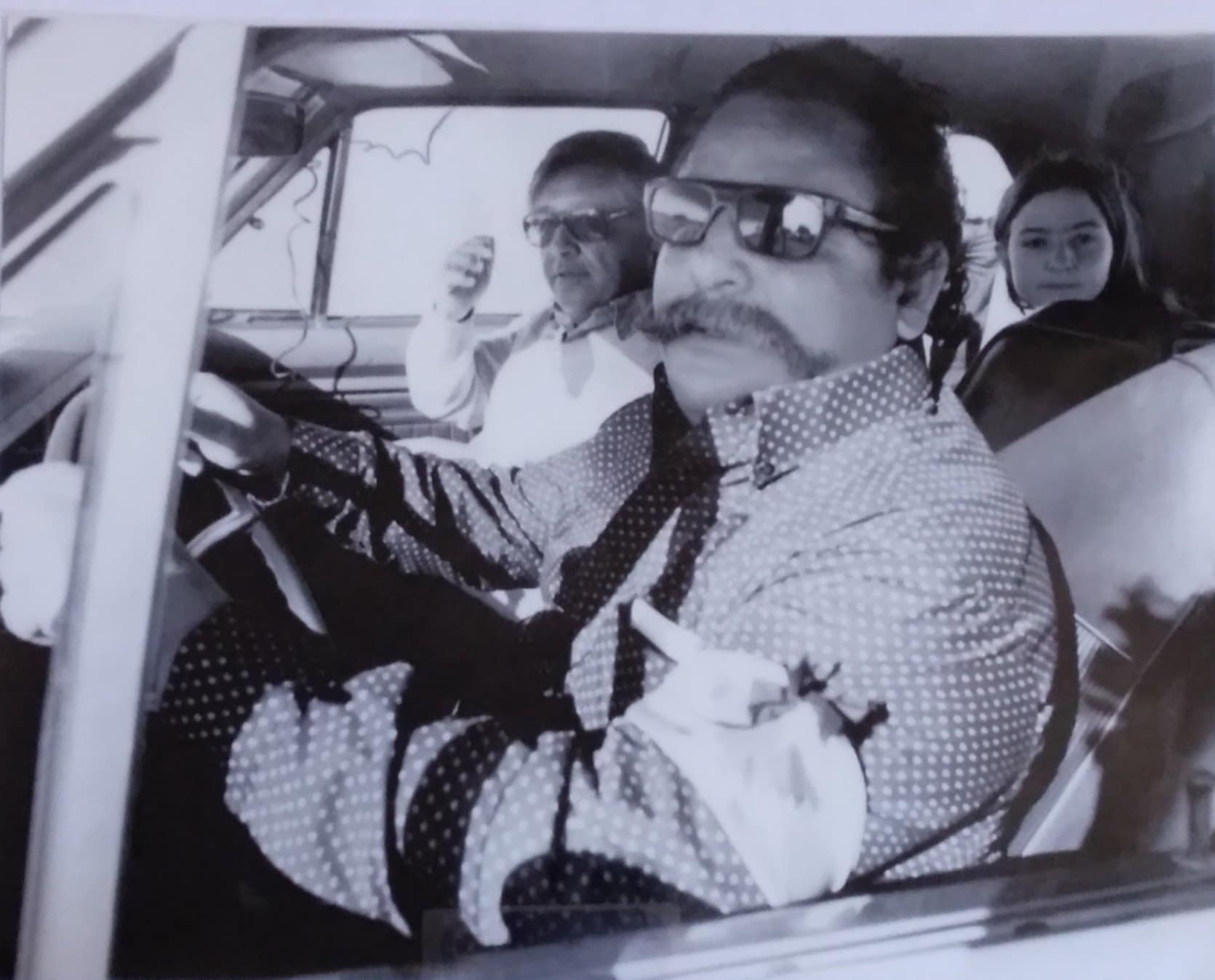

As we all gathered, small conversations grew into larger discussions. Los Amigos de la Comunidad, represented by Eric Reyes and Isabel Solís, spoke alongside Joseph Salazar, me, and others. One speaker who stood out was Robert Garcia, representing the Filipino community. His story will be shared in a full article soon, so keep an eye out for it. A few days after the meeting, Sarina and I met Robert and Max on the east side of Brawley. Robert gave us a ride around town as he reminisced about the valley’s untold history, while his old band’s music played softly from the CD player.

I attended one final meeting before the César Chávez March that Saturday at Las Chabelas. There, I met Julio Bracamonte Jr., a farmworker who shared a powerful story about his time in the fields. At some point during the César Chávez event, Julio gave me a handwritten story – it was the once-in-a-lifetime experience he shared with Sarina and I. It was also our first paper-based submission, which you can read about here.

Max stood at the head of a long table, offering words of encouragement and reflection to the group. Each of us received custom-made red shirts to wear in honor of the United Farm Workers (UFW), and afterwards, we gathered beneath a newly raised billboard promoting the event for a group photo.

That Saturday, Plaza Park in the heart of Brawley’s Main Street, I watched a pro wrestling match featuring Venue Wrestling Entertainment wrestlers, which was a fun way to kick off the day. Later, Sarina and I headed over to the march, beginning at Hinojosa Park. The turnout was strong, with more people than I had imagined. It was great to see millennials and Gen Z in attendance, including students from the IVC Chicano Studies class. We gathered together and recited the Prayer of the Farm Workers’ Struggle or…

Johnny Itliong, son of labor leader Larry Itliong, a key figure in the 1965 grape strikes, spoke about the sacrifices of farmworkers, emphasizing the importance of fighting for workers’ rights. As we began our walk, De Colores filled the air, and the weather was perfect. I spent most of the march talking with Julio, while Sarina captured footage for our video project.

The walk took about 15 minutes, ending at Plaza Park. Cheers filled the streets and everyone gathered together for photos. Miguel addressed the crowd, followed by Diego Galván, a second grader dressed as César Chávez for a school presentation. Las Flores Del Valle Ballet Folklórico, a mariachi group from Hidalgo Elementary School, and the Brawley High School Band performed for us, bringing Main Street alive that evening just before sunset. Sarina and I then headed off to enjoy the rest of the festivities at Inferno and Plaza Park that evening. Every performance that day, from the wrestling match, to Chávez celebration, and everything else in between, it’s a day that will be etched in my mind for the rest of my life, just because it was unlike any other. It’s really telling to me, if the weather was better during the day, then people would be out socializing more. It makes a lot of sense how important it was for residents of the Imperial Valley to have a night life back in the day.

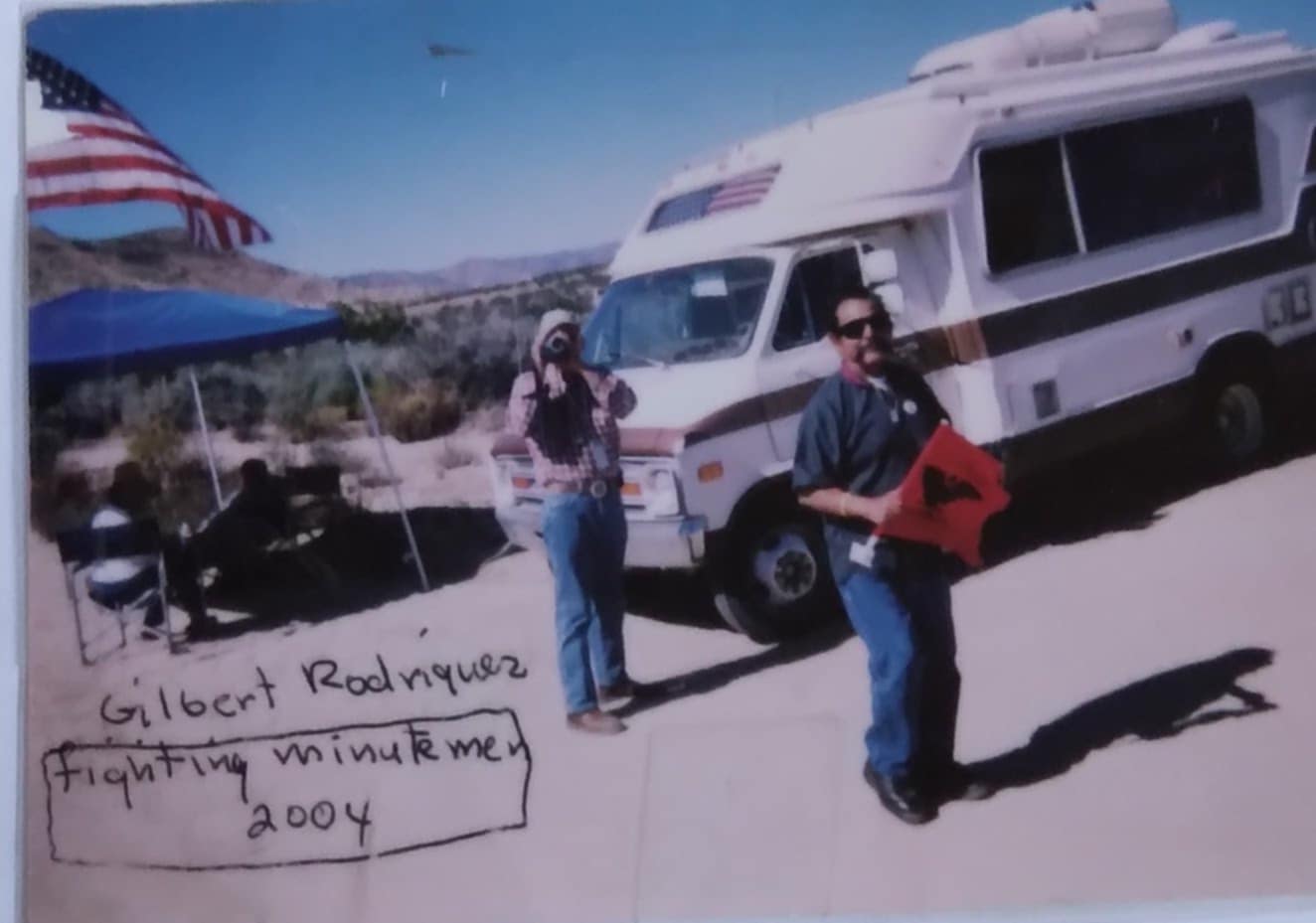

A few weeks later, I met Dianna outside a Starbucks in Brawley, where we talked about her father, Gilberto “El Bombero” Rodríguez, and his decades-long friendship with César Chávez. Dianna spoke of how her father started in the early organizing days. He was approached by Lupe Quintero, one of the early female organizers, who told him: “Gilbert, just help us.” He filled out union cards, grievance forms, and applications for assistance on behalf of field workers who didn’t understand English or didn’t know how to navigate the system. And when Chávez saw the dedication and leadership in him, that’s when it all began. Dianna emphasized that her father never turned people away by never seeing farmworkers as beneath anyone. He taught his children that degrading people based on where they came from was never acceptable. “If you’re going to call someone a ‘wetback,’ you’re hurting their feelings. They’re just like us.”

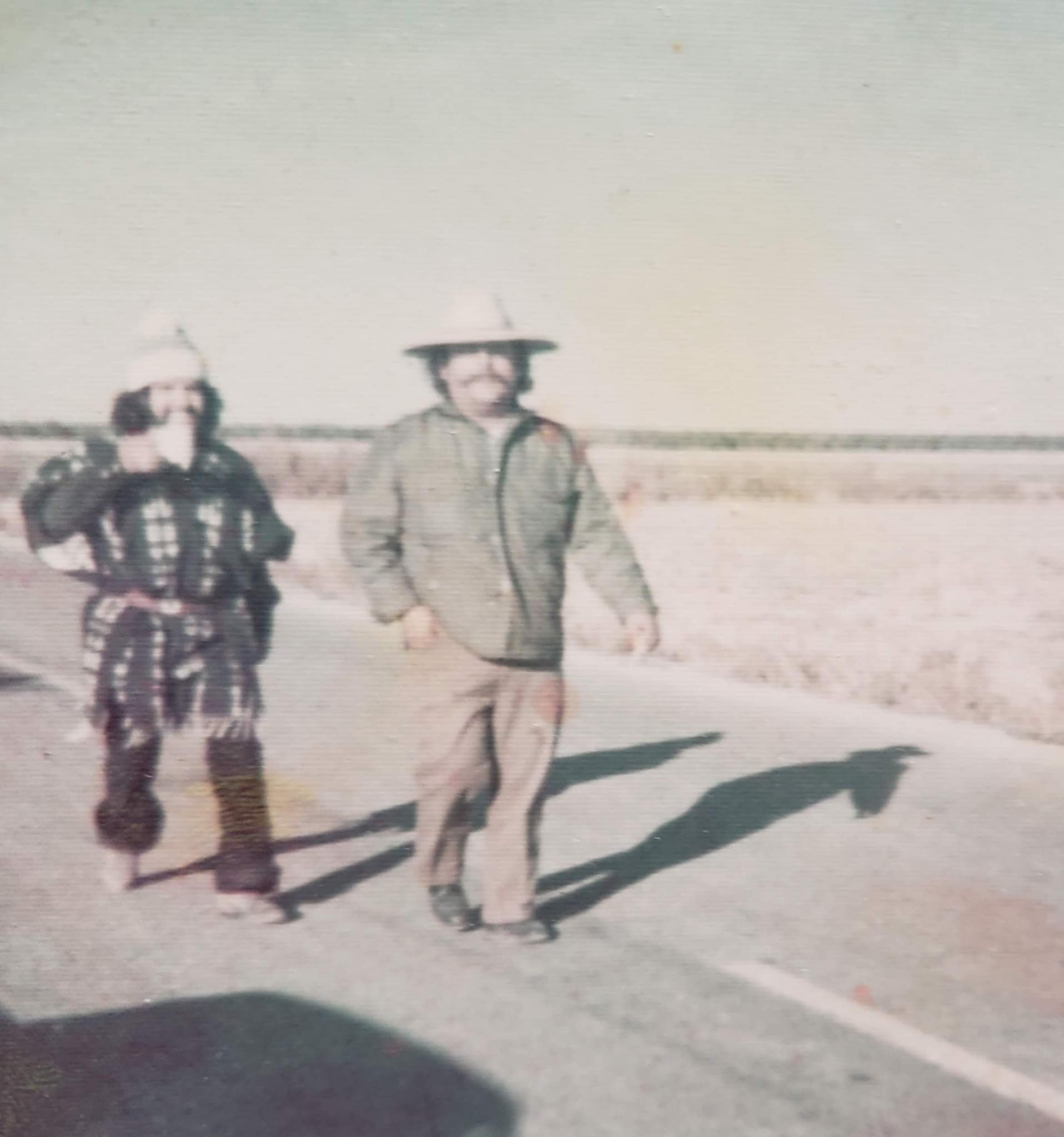

Photos courtesy of Dianna Morales

Photos courtesy of Dianna Morales

Dianna made sure I understood that, and even though her dad became deeply involved in the movement, he never abandoned them. “Some people say he did, but he’d still call, still visit, still show up for birthdays. He was our hero.” When they were kids, her sister Linda would cook meals for unexpected guests her father said were “just company.” It turned out to be César Chávez, Dolores Huerta, and others from the union. They’d sit in the home and eat together like family. They didn’t know how big it all was at the time. “It was just our life.”

Photos courtesy of Dianna Morales

Photos courtesy of Dianna Morales

There were special memories, like the day the whole family piled into a little Volkswagen taxi to go pick up a new car at Forty Acres. Dianna remembers all five of them in that car, heading to where so many workers had once gathered. They later went to Santa Maria for a union anniversary event, where they held the UFW flag as kids. Dianna still remembers seeing César’s German Shepherds, Boycott and Huelga. “They were beautiful dogs,” she smiled. “I tell my daughter, I wish I could go back to those times.” Because it wasn’t just politics, it was her childhood. “I learned not to degrade people. If you ever argue,” her father told them, “take care of it but without violence.” That’s how her father lived. When Dianna called Arturo Rodríguez, a union leader, after her father’s death, Arturo said, “We’re going to miss El Bombero.” At first, she didn’t get it. “You mean the firefighter?” Arturo told her, “Yes. Your dad put out fires…”

9:30AM – 5:00PM

Ties can be expensive, but the collection here is amazing. I’ve discovered designer ones, vintage ones, colorful ones, silk ones, cotton ones, and everything in between. I’ve also found some great blazers here, in addition to things here and there for my kitchen.

Photo courtesy of Gil Rebollar

Photo courtesy of Gil Rebollar

That stayed with her. She had always known her father was strong, but hearing that from a union leader decades later hit her deep. Dianna still remembers how César Chávez attended her sister Gloria’s quinceañera. He came quietly, flanked by guards who scanned the room. When all was clear, he entered, embraced the family, and left. Her father had been César’s driver, his guard, and his most trusted friend.

Photos courtesy of Dianna Morales

Photos courtesy of Dianna Morales

When Chávez once asked Gilberto to join the UFW board of directors, her father said no. He didn’t need a title. César was hurt, but he understood. What mattered more was loyalty. Dianna says she never saw her father cry, not when his parents passed, not when his brother died. But when César passed, the tears came. Dianna’s story showed me the human side of a powerful movement, in places like her home, a little Volkswagen taxi, or a family gathering. They’re the moments few ever experience. Meeting her reminded me why I tell these stories. These are people with a voice that should be heard, and People’s Press is the publication to do that. I want to keep these legacies alive.

Photos courtesy of Dianna Morales

I hear about César Chávez every year, but this year felt different, like a defining moment where I truly began to understand what the movement was really about and why it matters so deeply. It’s one thing to know the name, but hearing these personal stories and seeing the legacy through different eyes brought it all to life in a way I never expected.

This year has been different in another way too, and unfortunately, it hits a bit close to home. So, I’m going to get a little deeper with everyone now, and since we’re at the end of the story, why not? It’s worth asking what the results for this year’s ICE raids have been. I turn to Jesus Christ for guidance, and I’m reminded that the law has purpose, but it must be guided by compassion. So I’m left with this question: Are we living up to those values? I believe a better future starts with understanding our differences. We may not all agree on the path forward, but maybe we can agree that any solution must begin with…

Want to support Citizen Journalists like Justin?

☕️ Buy Justin a coffee! 😊